The Role of Schools in Supporting Children in Foster Care

Despite the pain, hardship, and disruption of their early lives, many foster youth are unbelievably resilient individuals. They grow up to become productive and connected members of society: they graduate from high school, college, and post-graduate schools; start successful careers; raise strong families; and contribute to their communities in valuable ways.

—Youth Transition Funders Group (2003, p. 9)

Introduction

Educators and policy-makers often say that education starts at home. Unfortunately, not all youth have the stability and opportunities afforded to children with intact families. Each year, more than 500,000 children are placed in foster care (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2008—whether in a foster home with non-relatives or with relatives, a group home, an emergency shelter, or a residential or treatment facility.

After they are removed from their biological homes, youth may change foster care placements multiple times. Each placement brings a new community and a different culture, which these youth must now learn to navigate.

Placement in foster care generally means placement in a new school. Changing schools is a disruptive process for any child, but especially for these children because of the many losses they have already suffered—their biological families, their homes, their friends, neighbors, and teachers, possibly even their pets and their favorite toys—on top of the abuse or neglect that brought them into foster care in the first place, and the new involvement of child welfare agencies and judicial systems in their lives.

Children in foster care also suffer from the very systems that are supposed to help them. Organizational bureaucracy and differing cultures among systems often create barriers that interfere significantly with the child’s education (e.g., delays in sending school or health records, and not allowing immediate enrollment in a new school because of this; not providing information about supplemental services the child needs). When there is ineffective communication between all agencies, or confusion among agencies’ roles, a child’s best interests may not be served.

Consider the following statistics from the National Working Group on Foster Care and Education (2008):

- Students in foster care score 16–20 percentile points below their peers in state standardized testing.

- Less than 60 percent of students in foster care finish high school.

- Only 3 percent of children who have been in foster care attend post-secondary education after high school graduation.

- Forty-two percent of children do not begin school immediately after entering foster care, often because of missing records and gaps in school attendance.

This brief provides Safe Schools/Healthy Students (SS/HS) project directors, staff, and community partners with strategies for collaborating with the child welfare system and other community partners to promote academic success for children in foster care. These strategies include facilitating collaboration among juvenile justice, mental health, and child welfare systems; providing supplemental educational services to youth; and providing training and guidance on state and federal legislation, policies, and programs that are specific to children in foster care.

Understanding the Child Welfare System

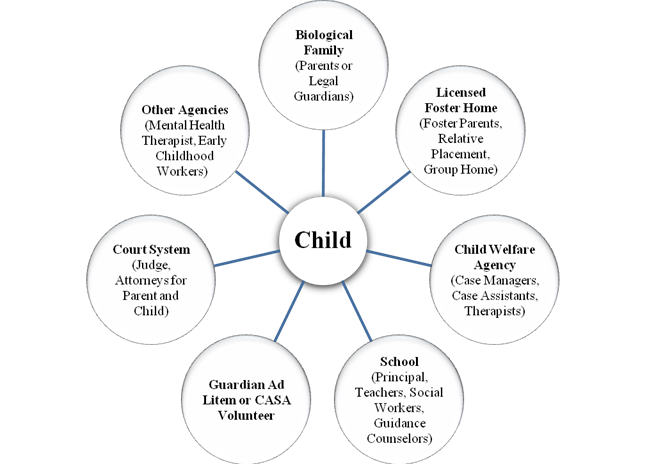

Children in foster care have a variety of people, agencies, and systems involved in their lives (see Figure 1). To effectively facilitate collaboration among these entities, it is important to understand the child welfare system as a whole as well as the other key players.

Figure 1: Key Players in the Life of a Child in Foster Care (Adapted from Lichtenberg, Lee, Helgren, & Bradley, p. 5)

When a child experiences abuse or neglect that is substantiated by an investigative agency, long-term parental illness, or incarceration of a parent, or when a parent voluntarily relinquishes his or her parental rights, the state child welfare agency recommends that the child either be removed from the home or remain in the home with support services. If the agency determines that the child should be placed in foster care, there is a preliminary protective or custody hearing with a judge. If the judge decides that the child has been abused or neglected, the case proceeds to an adjudicatory and dispositional hearing. At this point, the judge usually follows the recommendation of the child welfare agency regarding placement of the child.

Once the child is adjudicated, the family—the child (or children) and his or her parent(s)—becomes involved with juvenile or family court. The judge grants legal custody to the child welfare agency, and the family is assigned a caseworker who is responsible for developing a case plan. The primary objective of the foster care system is to provide short-term care with the goal of family reunification. The case plan outlines the steps the parent(s) must take to be reunited with the child. (For more information on what happens after abuse or neglect is reported, see A Child’s Journey Through the Child Welfare System in the Resources section of this brief.)

Throughout this process, the judge and child welfare agency are charged with acting “in the best interest” of the child. Although there is no universal definition for this term, it generally refers to “the deliberation that courts undertake when deciding what types of services, actions, and orders will best serve a child as well as who is best suited to take care of a child” (HHS, 2008b).

A guardian ad litem (GAL), lawyer, and/or court-appointed special advocate (CASA) is appointed by the court to represent the child’s best interests. This person advocates on behalf of the child during his or her time in the child welfare system. (For more information on a family’s path through the child welfare system, see A Family’s Guide to the Child Welfare System in the Resources section of this brief.)

Disruptions in School Stability

Prior to their foster care placement, some children have missed many days or even months of school, for a number of reasons:

- Eviction of the biological family

- Becoming homeless

- Moving from one home to another

- Parental substance abuse

- Lack of clean clothes to wear

- The parent or child’s desire to hide the physical marks of child abuse

Adapting to a new curriculum and school culture poses challenges to any child. Children in foster care, with limited resources to draw on, may stop attending school regularly, which increases their risk of academic failure. Other barriers to regular school attendance include the challenge of making new friends and the different expectations that biological and foster parents may have regarding education (e.g., the importance of attending school or working hard in school), which can be confusing for the child. Children who change schools also find it difficult to form relationships with school staff who could support their academic success.

Organizational bureaucracy can present another barrier to school attendance, as many schools will not enroll a student whose paperwork is missing or incomplete, and there are often delays in transferring needed school or health records.

The result of regularly missing school, having to change schools frequently, and having their enrollment delayed is that children in foster care are often academically and socially behind their peers. These disruptions in school stability increase the risk of academic failure and hinder educational achievement. Youth in foster care often have increased behavioral problems, require special education services, are at increased risk of dropping out of school, and/or have an increased risk of juvenile delinquency (Ryan & Testa, 2005; Zetlin, Weinberg, & Kimm, 2003).

The following vignette illustrates the many disruptions in school stability that can occur after a child is placed in foster care.

Adam’s Story

At age 13, Adam was removed from his biological father’s home due to neglect. He was placed with an aunt who lived in another town. Shortly thereafter, he got in trouble at school for possession of methamphetamine; at that point, Adam had been abusing different substances for about two years. After a 45-day inpatient treatment, his aunt refused to take him back, and there were no other relatives to take him, so Adam was placed in a non-relative foster home.

During the first four months of this placement, Adam’s behavioral problems escalated and the foster family could not handle him. A case management meeting was held, and it was determined that Adam needed a 30-day evaluation, so he was moved to an inpatient residential placement. As a result of the evaluation, Adam was moved up from regular foster care into “treatment or therapeutic care,” which resulted in a new placement in a therapeutic foster home. Adam was in this foster home for nine months.

Because of these many placements, Adam attended seven different schools in less than two years, and his educational continuity and success were significantly compromised.

At this point, Adam was placed back with his biological father. This lasted for almost two months, until a child welfare hotline call resulted in the state again taking custody of Adam. The home that Adam had lived in just before reunification with his father was full, so he was placed in a new therapeutic foster home.

Figure 2 illustrates Adam’s transitions in the first 19 months that he was in the custody of the state.

Figure 2: Disruptions in Adam’s School Stability (To learn more about a law designed to increase school continuity for all children who come into foster care, see The McKinney-Vento Act later in this brief.)

Strategies to Enhance Collaboration Between Schools, the Child Welfare System, and Other SS/HS Partners

The child welfare and education systems are both meant to promote the well-being of children and families, and each system has its own perspective on and approach to working with children and families. However, local child welfare agencies are not a “required” community partner for SS/HS grantees. Indeed, it is not common practice for school districts to form partnerships with child welfare agencies, typically because of the different requirements for the two systems regarding confidentiality and information-sharing, and a lack of mutual trust (Altshuler, 2003).

Nonetheless, effective collaboration among these systems can help in meeting the educational, physical, and mental health needs of youth in foster care (Zetlin, Weinberg, & Shea, 2006). It can move systems away from authoritative to shared decision-making that advocates for the complete child, which can help to ensure that the physical, mental, emotional, and educational needs of youth in foster care are addressed. Collaborating more effectively also enables systems to identify and overcome barriers that hinder the educational success of these children, resulting in improved sharing of critical information, fewer school transitions, and more timely school enrollment.

Before a child walks through the doors of a new school, he or she has already experienced many traumatic and disruptive events, including the original abuse or neglect, removal from the home, separation from siblings, having to tell and retell the story to strangers, meeting caseworkers, and meeting new foster parents. To enhance each child’s experience of continuity and security, the systems that interact with the child should communicate and collaborate as much as possible with one another.

Schools can use the following strategies to enhance collaboration with the child welfare system (as well as other relevant systems, such as law enforcement, mental health, and juvenile justice):

- Develop good relationships with senior supervisory child welfare agency staff. Because frontline child welfare caseworkers typically have high turnover rates, it is essential for school staff to develop trusting relationships with senior or supervisory staff members. Senior child welfare staff members can require their staff to collaborate with school staff on issues involving children in foster care. Senior staff can also help to facilitate policy changes and decision-making on important issues.

- Develop clear, consistent guidelines to facilitate information-sharing across systems. Federal and state legislation, agency policies, and professional codes impact how much and what kind of information about children in foster care can be shared with other agencies and organizations. The inter-agency agreement that SS/HS Core Management Teams develop can be extended to child welfare agencies and can include guidelines on how and with whom information regarding students in foster care can be shared. Children involved in the child welfare, mental health, education, substance abuse, and juvenile justice systems complete many different consent and confidentially forms. Developing a community-wide universal consent and confidentiality form can assist in facilitating the flow of information among all systems. (For more information, see Helping Foster Children Achieve Educational Stability and Success: A Field Guide for Information Sharing in the Resources section of this brief.)

- Clearly define each agency’s role. Although both child welfare caseworkers and school personnel work with the same children, they are often unclear about the other’s role. The SS/HS Core Management Team can sponsor “brown bags” (informal information-sharing sessions over lunch), where each agency describes its goals and strategies, as well as how it collaborates with other relevant systems.

- Hold regular case management or staff meetings with representatives from each system. This helps to decrease duplication of services and to increase the likelihood that children will receive wrap-around services tailored to their unique needs.

- Provide cross-training for all involved individuals and organizations. Each system offers its staff professional development. For instance, a mental health agency may offer workshops on children affected by trauma or the symptoms of childhood depression, whereas a school district might hold seminars on developing an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) or how to help children with attendance problems. Cross-training provides a forum for organizations to share policies and procedures, skills, and perspectives. Educating one another helps to reduce the tension between organizations, build partnerships, and improve the service delivery to children and families.

- To maximize the impact of cross-training, each organization’s training should be presented in a way that is welcoming and relevant to diverse professionals.

- Developing a memorandum of understanding or agreement between all systems that addresses cross-training issues can help to ensure that each party has access to a range of relevant training opportunities and to the same information and community resources.

- Inviting all the organizations and individuals who work with and advocate for children in foster care in a given community (e.g., states attorneys, court-appointed public defenders, CASAs, GALs, mental health professionals, educational advocates, caseworkers, and case assistants) to participate in cross-training can help them all become more effective educational advocates for these children.

- SS/HS project directors, with the support of their Core Management Team, can develop a shared community calendar or e-mail list that includes all relevant upcoming trainings or workshops.

For more information on effective collaboration, see School Mental Health and Foster Care: A Training Curriculum for Parents, School-Based Clinicians, Educators, and Child Welfare Staff in the Resources section of this brief.

Strategies to Promote Academic Success for Children in Foster Care

Schools and child welfare agencies can adopt policies that ease the school transitions of children in foster care and improve their chances of academic success. Here are some examples of policies and guidelines that are useful in supporting successful school transitions:

- A policy that addresses how school transportation costs will be paid (i.e., by one agency or shared between agencies) for youth whose foster parents live in another school district

- A policy that ensures immediate enrollment even if there are missing required educational, health, or special education records

- A policy that expedites convening a special education meeting if the child needs to receive services immediately through an IEP or 504 plan

- A policy about information-sharing that clarifies what information can be shared about the child and with whom

- Guidelines that outline the roles and responsibilities of support staff and foster care parents when enrolling a child in a new school

The following are additional strategies that schools and school districts can employ to promote educational stability and academic success for children in foster care:

- Hold regular meetings with an education team of school staff and staff from other agencies involved with the child (e.g., caseworker, teacher, guidance counselor, mental health professional, social worker, juvenile probation officer, special education liaison, Big Brother/Big Sister mentor, educational advocate) to discuss the child’s educational progress and needed resources and services.

- Once notified by the child welfare agency that a child will be moved to another school district, the original district should expedite the forwarding of school records so that the child may be quickly enrolled in the new school. As appropriate, staff in the new district should receive a call to identify any special services or resources the child requires so there is no gap in services.

- Involve the child’s caseworker, GAL, CASA, birth parents, and/or caregivers, as appropriate, in education planning.

- Identify a school staff person (e.g., counselor, teacher, social worker) whom the youth can talk to about any problems or concerns.

- If the child has fallen behind his grade level, provide partial credits and opportunities for credit recovery and/or assign a tutor.

- Reduce out-of-school time by referring the child to school-based health and mental health services.

- Build time into the child’s schedule to make up work he or she missed when out of school for health care and mental health care appointments, as well as visits with biological parents, siblings, and caseworkers.

Supplemental Education Services for Children in Foster Care

Case managers are required to develop a case management plan as soon as a child comes into foster care. The case management plan typically covers an assessment of the needs of the child and family and a plan to meet these needs, including coordinating linkages to health care, social and emotional support, and other services. The case manager tracks and monitors the progress of the child and family. A timeline is usually included in the plan that indicates what the parents must do to have the child placed back in the home.

The Fostering Care Connections to Success and Increasing Adoption Act of 2008 mandates that case management plans for foster care youth must include an educational plan that addresses educational stability. Simply put, placement considerations must take into account where the child will attend school. When the school and the child welfare agency jointly develop the education plan for a child in foster care, the likelihood of educational stability is enhanced. Additionally, because children in foster care have higher rates of chronic medical problems and developmental, emotional, and behavioral disorders than other children (Percora, Jensen, Romanelli, Jackson, & Ortiz, 2009), effective collaboration between the school and other agencies is critical to ensuring that all providers know which programs and services are available and are being provided to the child.

Preschool-Age and Younger Children

Children who participate in high-quality child care and preschool function at higher levels in early elementary grades than children who do not (Lunenburg, 2000). Children who enter foster care in early childhood typically have not been exposed to early childhood or preschool programs, or interactions with early childhood professionals. This places these children at a disadvantage, especially if they have experienced developmental delays.

A 2005 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services longitudinal study of more than 6,200 children who had contact with child welfare agencies found that 53 percent of the children ages 3–24 months whose families were investigated by child protective professionals for abuse or neglect were classified as at high risk for developmental delays or neurological impairments (HHS, 2005). Some children in foster care qualify for services under Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which provides grant funding to states for comprehensive statewide early intervention programs and services for infants and toddlers (0–2 years) and their families. Children in foster care who qualify for Part C receive services to meet their educational, mental, and physical needs in a school or home setting, such as occupational, physical, and speech therapy; hearing and vision screening; psychological, social work, and nursing services; nutrition counseling; and assistive devices.

The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), as part of a reauthorization under the Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003, is a federal law that requires states receiving funding from Part C of IDEA to refer children under the age of 3 who have experienced a substantiated case of child abuse or neglect to early childhood intervention services or programs for evaluation and screening. School staff familiar with Part C (e.g., special education directors, early childhood staff, guidance counselors, social workers) can communicate with case managers about programs and services available through the district for toddlers and children who do not qualify for other programs. (For more information on how states implement the referral provisions under CAPTA, visit http://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/partc/index.cfm.)

School-Age Children

While 10 percent of the entire student population receives special education services, children in foster care are over-represented in this group—33–50 percent of children in foster care receive special education services (Zetlin, 2006). This may be because schools don’t have other appropriate programs and services (or partnerships with relevant community agencies) to address the academic and behavioral issues of children in foster care. School staff may also believe that the trauma these children have experienced necessitates intensive services for each of them (Zetlin, 2006). However, while many children who come into foster care do require special education, others are inappropriately identified as needing these services.

When a child with an IEP must change foster care placement and start a new school, it is critical that these records are immediately transferred with the child. The school should work with the child welfare agency to ensure a seamless transition of all needed school and health records.

Youth in foster care typically do not have an involved biological parent who advocates for their educational needs. Caseworkers and foster parents often try to fill this role, but an incomplete understanding of the child’s history and/or of how the education system works can make it challenging. Elementary school-age children in foster care rely on child welfare and education professionals to advocate on their behalf. Middle and high school youth, on the other hand, can become empowered to become their own educational advocates, participating in school meetings, special education placement discussions, and transition planning. Schools can help older youth to find their voices and to advocate for themselves.

Federal Legislation that Supports Children in Foster Care

Although state agencies govern the structure of the state’s child welfare system, they must also comply with federal requirements in order to be eligible for federal funding. Given the complexities of child welfare legislation, SS/HS project directors and other school staff should keep in touch with their local child welfare agency about the impact of federal legislation on children in the community. Project directors may want to consider inviting state child welfare agency professional directors to an annual meeting to discuss legislation and policies that impact children in the community who are in foster care.

The McKinney-Vento Act

Advocacy groups are working to achieve policies that increase school continuity for all children who come into foster care. When the child’s safety is not an issue, keeping the child in his or her home school is often the best practice.

The 1987 federal McKinney-Vento Act aims to improve school stability for children who are homeless by providing access to their school of origin (the school that the child attended prior to becoming homeless), transportation to the school that the child last attended, and immediate enrollment upon entering a new district regardless of missing school records or other information.

The act defines homeless children as individuals who lack a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence, including children who share housing with other families; live in motels, hotels, camping grounds, emergency shelters, cars, parks, abandoned buildings, or any other public space that is not ordinarily used for sleeping; and children awaiting foster care placement (The Legal Center for Foster Care, 2009). However, because the legislation does not offer a definition for “awaiting foster care placement,” each state develops guidelines for its school districts about which students fall into this category.

The law mandates that all states have a State Coordinator for Homeless Education, who is responsible for helping school districts comply with the McKinney-Vento Act. A list of all state Coordinators for Homeless Education can be found at http://center.serve.org/nche/states/state_resources.php.

Other Federal Foster Care Legislation

Following is a list of other legislation related to education and children in foster care. For a complete list of federal and state child welfare legislation and summaries of the laws listed below, visit the Child Welfare Information Gateway at www.childwelfare.gov.

- Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-351): Requires that the case management plan for each child in foster care include a plan for educational stability. For more information, see http://www.nrcpfc.org/fostering_connections/

- Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-36): Addresses issues related to referring children under age 3 for whom there is a substantiated case of abuse or neglect for early intervention services that are funded under Part C of IDEA.

- Promoting Safe and Stable Families Amendments of 2001 (P.L. 107-133): Authorizes a voucher program, the John H. Chafee Foster Care Independence Program, which offers services to youth in foster care who have aged out of the system.

- Foster Care Independence Act of 1999 (P.L. 106-169): Includes state grants and expanded opportunities for youth aging out of the foster care system in the areas of education, training, and employment services and financial support to prepare these youth for independent living.

- Multiethnic Placement Act of 1994, amended by the Interethnic Provisions Act of 1996 (P.L.104-188): States that individuals cannot be prevented from becoming foster or adoptive parents and that children cannot be denied foster care or adoption placement on the basis of race, color, or national origin.

- Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-608): Enacted to keep American Indian children with American Indian families. For more information, visit the National Indian Child Welfare Association at http://www.nicwa.org/Indian_Child_Welfare_Act/.

Conclusion

By collaborating with the local child welfare system to ensure a coordinated effort that provides seamless educational transitions, and by working to ensure that children’s physical, mental, emotional, and educational needs are met, SS/HS project directors, staff, and community partners can play an important role in supporting the academic success of children in foster care.